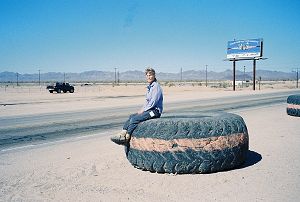

The Glamis Store |

These barriers make nice benches too |

This granddaddy of all U.S. dunes stretches 45 miles from east of Calipatria in Imperial County to near Los Algodones in Mexico. And, at an average of six miles, they are quite wide too. Highway 78 crosses the dunes at Glamis. The dunes are also known as Imperial Dunes or Glamis Dunes.

For many years, the dunes have been a barrier to the movement of people, first on foot and later by car. In 1915, a wooden plank road was built across the dunes to facilitate travel between Yuma and San Diego. A section of the road can be seen in The Yuma Crossing Historical Museum.

During World War II, desert warfare training was conducted on the dunes. People have been driving on the dunes for recreation almost since vehicles first reached the area. On any three-day weekend, the dunes are host to upwards of 100,000 dune buggy enthusiasts. No wonder the sign at the Glamis Store proclaims it as the Sand Toy Capital of the World.

The Glamis Store |

These barriers make nice benches too |

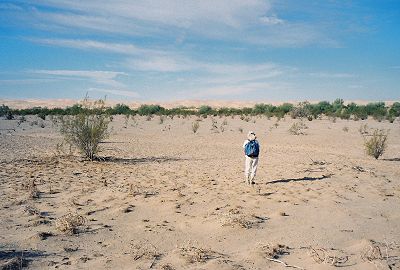

The dunes south of Glamis are open to off road vehicles, whereas most of the northern portion is designated as wilderness. Our taste runs a bit differently than those wanting to ride the dunes, and we were content to be on the quiet side. A dirt road runs parallel to the dunes on its east side and it provided us with a means to get away from the noisy environment of Glamis. However, the high dunes are on the west side. We needed to walk about four miles on the low vegetated dunes to get there.

Aren't we there yet?

The tall dunes acted as a wind barrier, and it felt quite hot as we trudged along. What a relief and delight it was to finally get on the high dunes. The breeze cooled us and the 200-foot tall dunes provided us with good vantage points. We spent a couple of hours traversing the coarse sand ridges and were glad that we had made the effort to get to the tall dunes.

A view from the tall dunes

We returned to our car in the late afternoon. These were the last desert dunes on our list and we were mentally relaxed. But not for long. Would you believe another tire blowout? And on a well graded dirt road?

In the past, Joy and I had driven some really bad roads. The two that come to mind are Lippincott Grade - Saline Valley Road and Berdoo Canyon Road.

Lippincott Grade connects the Racetrack area of Death Valley National Park to Saline Valley below. It is a steep, one-lane dirt road and the signs advise that no tow truck service is available. I have heard that some disabled vehicles are just pushed into the deep canyon that borders the road. We drove in the lowest gear and in low 4x4 with one foot firmly on the brake pedal to slow the descent. The current maps don't even show the road, though the earlier maps do. Then we spent three hours negotiating 15 miles of pure driving hell, also called Saline Valley Road. But, we came out unscathed.

The Berdoo Canyon Road is a "short cut" from Joshua Tree National Park to Indio. This road heads south, drops into the mouth of Berdoo Canyon and begins a long descent, turning and twisting down the wash. The first seven miles are extremely difficult; big rocks, considerable sand and many wash-outs make driving it a real adventure. I remember walking off and on a mile of the most difficult section. I would scout the road and tell Joy the best way to proceed. At one point, both of us spent fifteen minutes getting a boulder out of the way. The "short cut" took us longer than the longest route back, but we never had a flat.

Surprisingly, the two questionable tires I purchased during the trip performed just fine. The two blowouts and one flat that couldn't be repaired were all on my Continental brand SUV tires. By the time we had our third blowout, I had become well versed in the art of changing a tire and buying a replacement. All the tire problems occurred at low to moderate speeds and our lives were never in danger. However, I was a bit apprehensive as we drove home. We were on paved roads but driving 500 plus miles at highway speeds on four different tires is not my cup of tea.

We now had just one dune left to visit, a coastal dune system not too far from our home.

Of the 27 dune fields in coastal California, the largest are the Monterey Bay Dunes, covering approximately 40 square miles. The major portion of the dunes lie north of Monterey, near Marina, Sand City and Seaside. The dunes are not too tall, especially compared to their counterparts in the desert. The dunes are constantly changing from wind and wave forces. During especially strong winter storms, this change can be quite obvious along the foredune. Beyond the storm-wave run-up area the rate of change is less perceptible. The reason for this is the native plant cover that has evolved with and adapted to these "shifting" sands. This living blanket insulates the dunes from the constant erosional force of wind. Unfortunately, heavy sand mining activity in the past destroyed most of the plant cover. To allow the vegetation to grow back, most of the dunes are off limits to people. In addition, the threatened Western Snowy Plover, a small bird, uses the dunes as its breeding ground. During its breeding season, mid-spring to mid-fall, many coastal dunes are closed to the public.

I was well aware of these restrictions but hoped to find at least some stretch of dunes we could walk on. We drove to several possible dune areas. All of them were fenced off and posted with "closed" signs. But, at the end of Dunes Drive, off Reservation Road, in the town of Marina, we finally hit pay dirt. Just to the right of the path leading to the beach, we encountered dunes that had no signs prohibiting entry. We continued northwards and were mostly on a small strip of dunes bordered on the east by a sand mining operation. We probably were on private land at least part of the time, but it was hard to tell.

Shouldn't this be a part of the town of Sand City?

After about three hours, we descended to the beach and returned to our car. We had a beautiful clear day to enjoy the dunes and the temperature, unlike in the desert, was just about perfect. It was a fitting climax to our quest to hike the wonderful world of sand dunes.

Dinesh Desai

March 2007