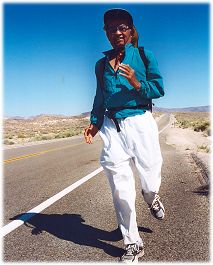

What's he trying to prove? |

That's what awaits a runner in the desert |

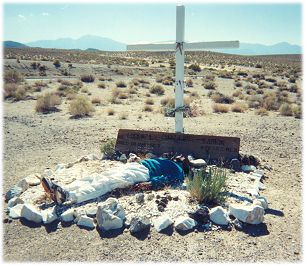

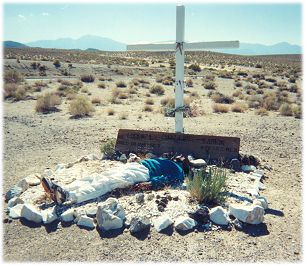

Our destination that day was a roadside pullout marked by a large gravesite. I was feeling good and as the gravesite came into view, I ran the last few hundred feet to the surprise of Harold and Ron.

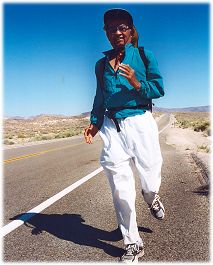

What's he trying to prove? |

That's what awaits a runner in the desert |

After surviving the first four days in the desert, we knew that Day 5 was going to be easy sailing. There was hardly any uphill and the downhill was quite gentle. And at 4,000 ft. elevation, the temperature was not likely to exceed 90°F. Was that day then one of my more enjoyable days? Surprisingly, no. Human beings can go from being stressed out to being bored in a very short time and that's what was happening to me. As long as I was on the edge, I was striving to overcome the adversity and putting on my best effort, and I was happy. But as soon as the pressure was off, I found myself somewhat bored.

I passed the historical marker announcing Cerro Gordo. Cerro Gordo was a silver mining town high in the Inyo Mountains and was well known for its extremely rich ore containing silver. Cerro Gordo's major development took place in the early 1870s. The town was producing 100 to 150 83-pound bars of silver-lead each day. These bars were shipped in huge wagons to the nearest ocean port city, which happened to be Los Angeles. At that time, Los Angeles was a sleepy pueblo and the now-dry Owens Lake had 50 feet of water. But Los Angeles grew and it built an aqueduct to transport water from the Owens Valley. Owens Lake, once a navigable body of water, and approximately fifty miles of the Owens River were completely dry by 1924.

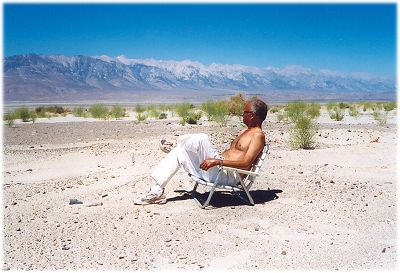

Dinesh enjoying "world famous" Owens Lake (no kidding; that's what a tourist brochure claims) |

As I was relaxing in my room after finishing the day's walk, I heard a knock on the door. I looked through the window and saw Ron standing near the door. I ushered him in.

"I have some good news," he said. "I checked with the Forest Service office in town and they have permits available to day-hike Mt. Whitney."

"Ron, I don't know whether I am strong enough to do it in a day. I did it in a day a few years ago but I was well rested and acclimatized to the altitude. It's different this time. We will have a 5,000-foot day before the climb and I haven't been to any high mountain this year. And because of my poor night vision, I don't look forward to walking at night either. That's why I had insisted on applying for a 2-day backpacking permit in the first place. So, let's just stick to our plan."

There are two common ways of climbing Mt. Whitney. One is by day hiking: starting from Whitney Portal around two a.m. or so, getting to the top in eight to ten hours and returning by six or seven p.m. The other is to backpack, spending a night half way up the mountain and taking two days instead of one. The advantage of day hiking is that one doesn't need gear such as a sleeping bag or a tent and doesn't need to carry a heavy backpack. It is also easier to get a day hiking permit. The daily quota is 150 for day hiking but only 50 for the overnight backpacking. The advantage of backpacking is that it allows the climber to acclimatize and breaks up the climb in two segments. An additional advantage for me would be not needing to walk at night. Most backpackers make it to the summit whereas many day hikers fail to reach the top.

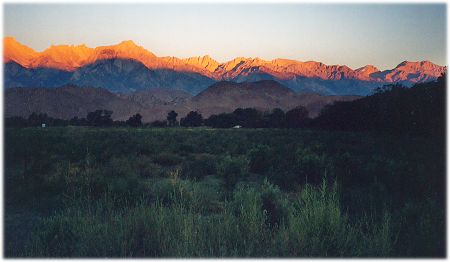

Mt. Whitney at sunrise |

I was in a real dilemma. I wanted to climb Whitney badly, but I was also aware of my limitations. After discussing with Ron the idea of doing Whitney in a day, that feeling of boredom I had earlier in the day seemed to have completely evaporated. Instead, it was replaced by anticipation and apprehension.