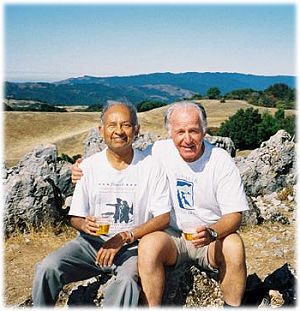

Don Hildenbrand's World War II Memoir of a GI

excerpted by Dinesh Desai

I graduated from high school in May 1942, and six months later I was drafted into the Army. In October 1944, I landed in Marseille, France with the 100th Infantry division. We moved 500 miles north by truck and began a sustained attack to break the German lines. Nothing in our training could have prepared us for the shock of that first artillery barrage from the Germans. It seemed to last forever, and the confusion, the dead bodies and the screams of the wounded unnerved us all greatly.

Our battalion captured a number of towns, and occasionally we had the luxury of sleeping in barns rather than in the cold, muddy fox-holes. In early January, our platoon moved to new front-line positions north of Rimling, close to the German border. A day later, just after midnight, several hundred German infantry attacked toward Rimling, bypassing our platoon's position. We were now cut off and without communication, as the telephone line was apparently severed. Our leader called for a volunteer to go back to the Command Post, to re-establish communication. When no one spoke up, I volunteered, hoping that my experience as a cross-country runner would be a plus. It was dark and I was not familiar with the area and so I followed the telephone line. That turned out to be a big blunder. As I found out later, a German tank was sitting astride the telephone line that I was following. I had walked right by the enemy camp. They fired at me. Luckily, I was not hit, but I was now a prisoner of war (POW).

Next day, we were herded into box cars for the trip to the German interior, near Frankfurt. As I jumped out of the box car at our destination, my frozen feet had no sense of feeling and I fell on my face, as did other POWs. We were put to work on a construction project. We were housed in flimsy huts, each holding 30 to 40 men. We slept on wooden planks covered with straw, and before long, we were all thoroughly infested with lice. We worked from dawn to dusk, seven days a week, doing hard manual labor. We had little time to rest and nothing to eat during the workday. Before work, we received only a cup of coffee, and after work, a loaf of bread to be split among ten men. Occasionally, there was a cup of thin soup. There were a number of deaths among the POWs. We all expected that the war would be over by now, late March, but many were quite despondent. Three or four of these men simply died in their sleep. On the surface, they seemed no less physically healthy than the rest of us; they simply had given up. I was determined that I was going to make it back, if at all possible.

In early April, with the fall of Germany imminent, the camp was evacuated and we headed south on foot. Our numbers had dwindled from 360 to 320, and the hard march and lack of food was taking its toll. When we would stop near some farm village, the German civilians would try to give us scraps of food, but the guards angrily pushed them away or knocked them down. We had walked maybe 150 miles, and were beginning to hear sounds of artillery fire in the distance, but coming ever closer. On April 23, 1945, a date forever etched in my memory, a column of tanks with big white stars came into view. Hallelujah! We were back under U.S. control.

At the hospital, I weighed in at 90 pounds, down from my normal 160 pounds, typical for everyone. We ate very sparingly, despite our great hunger, to give our intestinal system a chance to recover. My overall condition was improving rapidly, with no major damage apparent. My badly frost-bitten feet were continuing to give me trouble, but the prognosis was that they would heal completely in time.

I was reunited with my family in June and enjoyed a wonderful summer. I was pleasantly surprised to receive the Silver Star Medal for my ill-fated attempt to seek help for my platoon that fateful night near Rimling. Possibly, my experience did encourage the others in the platoon to seek escape by a different route than the one I had taken, but they did escape capture.

In retrospect, service in World War II was clearly one of the most significant events of my life. I think we can all take pride in what was accomplished. Even now, however, I find it difficult to think back about those who did not come back, without deep feelings of warmth and sorrow. In my view, they were the real heroes, and we all owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude for the wonderful lives we've had over the last half-century.