by Dinesh Desai

"This is our chance, Dinesh. Let's go for it."

"All right, Ron. But let's be careful and not stumble no matter how many rocks hit us. The water seems to be moving awfully fast further ahead."

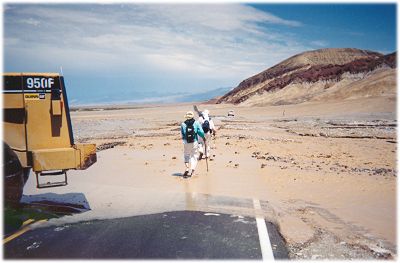

As we started crossing the road, I looked apprehensively at the mud and rocks pouring over it from a wide ditch swollen with the flash flood. At one point, the water was over a foot deep, but we made it across without any problems. I wanted to remove my shoes and get the sand and stones out, but instead, decided to keep going. The rangers on the other side had told us not to attempt to go across the flooded road and probably weren't too happy to see us ignore their orders. We had to cover 25 miles that day and could ill afford to sit around a couple of hours while a grader cleared the road.

Ron and Dinesh crossing the flooded roadway |

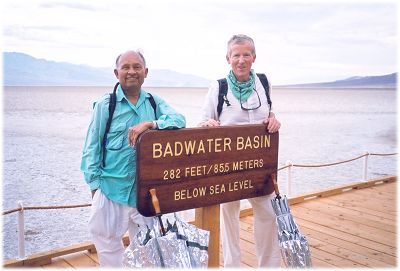

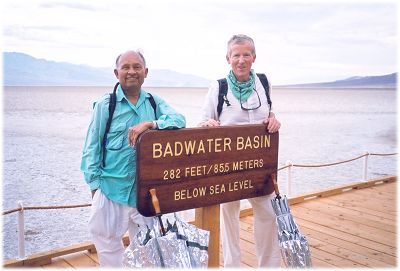

Ron Perkins and I had started our "lowest to the highest" walk on July 31, 2003 at 6:30 a.m. from Badwater Basin in Death Valley. Badwater is at an elevation of -282 feet (282 feet below mean sea level) and is not only the lowest point in the U.S. but is also the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere.

The lowest points of the continents

* The elevation of bedrock is 8,327 feet below sea level. However, the thickness of ice over it is 14,223 feet. Thus, a person standing on the ice over the lowest point would still be at an elevation of 5,896 feet above sea level. |

Our original plan was to walk from Badwater to the top of Mt. Whitney, approximately 150 miles to the west. Mt. Whitney, at 14,497 feet above sea level, is the highest mountain in the 48 contiguous states. A road goes all the way from Badwater to Whitney Portal, elevation 8,360 ft. A 22-mile round trip journey on a trail is then required to climb to the summit and return to the trailhead at Whitney Portal. Because of heavy demand to climb the mountain, the Forest Service issues permits to limit the number of climbers. It issues the permits by a lottery system and unfortunately, we weren't chosen. Disappointed, but still determined, we settled on an alternate plan.

By nine in the morning, heavy clouds covered the entire region. Soon, light rain began to fall. The summer thunderstorms had hit Death Valley. The Amargosa Mountain Range, which flanks the eastern side of the valley, was being hit with thunder and lightning and probably a much heavier rainfall. By 10:30 a.m., the clouds had dispersed and the sun was trying to come out. Ron and I tried to use our sun-reflecting, mylar-coated umbrellas, but the strong headwinds made it impossible to use them effectively. But that was a small problem compared to what was in store for us a little ahead. The flash flood unleashed by the thunderstorm had washed out the road. A flash flood is a sudden local flood of great volume, but short duration, and the deserts are particularly prone to them, as there isn't much soil to absorb the moisture.

On a clear day, the sign seems silly; but as we found out, flash floods do happen in Death Valley |

Flash flood near Golden Canyon |

We ignored the rangers' warning and made it across, but Harold, driving our support car, was stuck there for a couple of hours. He was our lifeline. The biggest problem a hiker encounters in Death Valley, or for that matter, any desert, is the need to consume a large amount of water and at the same time, the unavailability of it from natural sources. If Harold didn't meet us every six or so miles to replenish our water supply, we would have had to carry three plus gallons of water for our typical 24-mile day. The weight of the water plus the food and the pack would then be well over 35 pounds. That, in turn, would have slowed us down considerably and resulted in our needing even more water. Wouldn't we have needed less water if we walked at night? Yes, but we didn't want just to go from point A to point B; we wanted an adventure. Our self-imposed rules dictated that we walk in daytime and during one of the two hottest months of July and August. The whole idea behind the walk was to brave the heat, not escape it.

As I approached the support car parked at the 25-mile mark, I was somewhat disappointed. The thunderstorm had cooled the valley and the high that day didn't even approach 110°F. That's probably plenty hot for most people, but I was expecting temperatures above 120°F. However, the thunderstorm rewarded us with a first hand experience with a flash flood, showing us the incredible power of nature.

Why is Death Valley so dry and hot?Winter storms moving inland from the Pacific Ocean must pass over mountain ranges to continue east. As the clouds rise up they cool and the moisture condenses to fall as rain or snow on the western side of the ranges. By the time the clouds reach the mountain's east side, they no longer have as much available moisture, creating a dry "rainshadow". Four major mountain ranges lie between Death Valley and the ocean, each one adding to an increasingly drier rainshadow effect. The depth and shape of Death Valley influence its summer temperatures. The valley is a long, narrow basin 282 feet below sea level, yet is walled by high, steep mountain ranges. The clear, dry air and sparse plant cover allow sunlight to heat the desert surface. Heat radiates back from the rocks and soil, then becomes trapped in the valley's depths. Summer nights provide little relief, as overnight lows may only dip into the 90°F to 100°F range. Heated air rises, yet is trapped by the high valley walls, is cooled and recycled back down to the valley floor. These pockets of descending air are only slightly cooler than the surrounding hot air. As they descend, they are compressed and heated even more by the low elevation air pressure. These moving masses of super heated air blow through the valley creating extreme high temperatures. Although many factors have created a desert in the southwest, Death Valley's unique geographic features cause desert conditions to become extreme. Death Valley has the hottest and driest climate in North America. Year 1996 had 40 days over 120°F, and 2001 had 154 consecutive days of over 100°F. The second highest temperature on record, 129°F, was recorded on July 17, 1998 and guess what? Yours truly was walking there at that time. To read more about it, follow the link provided at the end of this account. |

As we returned to our rooms at Furnace Creek Ranch, we were informed that the thunderstorms had knocked out the power and that there was no air conditioning in the rooms. Everyone was given the option to check out and go to motels in towns across the border in Nevada. Many of the tourists just sat there dazed, but for us, sitting in a non air-conditioned room was still a lot cooler than walking in the heat.